Reuters

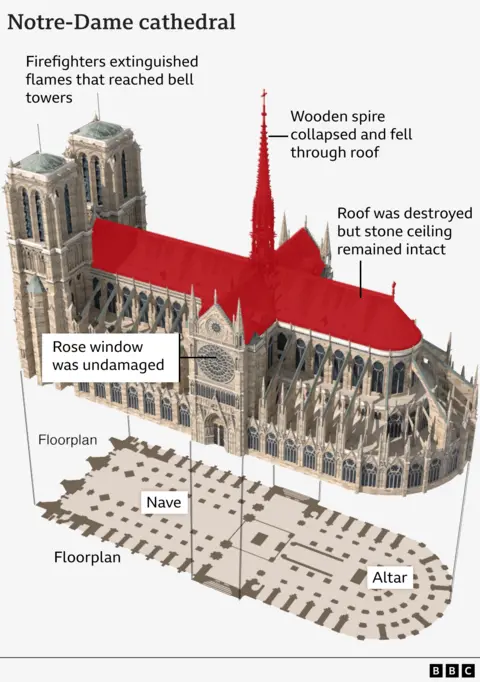

ReutersFrench President Emmanuel Macron has toured Paris’s Notre-Dame cathedral live on TV, giving the public a first look inside the building since much of it was destroyed or damaged in a huge fire in 2019.

From the spire to the stained glass, it has been completely transformed. It is not just a renovation after the fire, but a complete overhaul including removing decades of crud and soot built up since the last restoration.

Here we take a look at some of the key features of the repair work and how it was achieved.

The return of the spire

The collapse of the spire was the climax of the 2019 fire. Many people thought it was medieval, but in fact the original was taken down in the 1790s because it was deemed dangerous.

Its replacement, which burned down five years ago, was put up decades later as part of a neo-Gothic reconstruction conducted by architect Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc.

This time, carpenters used a mix of the traditional and the computerised to design and build the massive wooden base.

It was lifted into place by Europe’s largest crane, then a scaffolding shell was mounted allowing workers to assemble the steadily rising structure.

Like the rest of the roof, the spire is lined with lead. At the top a new gilded cock has been fitted to replace the original that fell in the fire. It was recovered but was too damaged to go back.

Inside the new cock are holy relics including a thorn from the cathedral’s Crown of Thorns, and a parchment with the names of 2,000 people who worked on the renovation.

Luminous limestone

The most striking feature of the renovated cathedral is the luminosity of the stonework. This is because all the limestone blocks have been cleaned, or in some parts replaced.

Replacement stone was sourced in quarries in northern France. Experts were able to detect tiny features in the original stone – like certain fossils – that helped them to determine the geographical origin.

The vast majority of the masonry was undamaged, but it was covered not just in age-old accretions of dust and dirt from the past, but also in a layer of soot and lead powder from the fire. It was cleaned with high-power vacuums, and then with a spray which peeled off to remove the dirt.

Overall some 40,000 square metres of stone were cleaned.

To rebuild the vaulted ceiling beneath where the spire had stood, masons had to relearn the principles of Gothic architecture – using a wooden frame to put the stones in place and crowning it all with the keystone.

More than 1,000 oak trees

EPA

EPAIt was the wooden roof that burned – all 100 metres of it. None of the 800-year-old timbers survived. But the decision was quickly made to replace them as faithfully as possible – with oak from the forests of France.

By happy coincidence an architect called Remi Fromont had conducted an in-depth study of the timber frame as part of his university thesis. This served as a template for carpenters.

Some 1,200 oak trees had to be found, with the stipulation that they be straight, free from knots and a condition called “frost-crack”, and 13 metres long.

Much of the wood was hand-sawn then hewed into shape with axes, just as the beams were in the 13th century.

Altogether there are 35 “fermes” (the triangular structures that take the weight) running the length of the building.

Digitally-scanned gargoyles

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany of the exterior sculptures – including the famous (but not medieval) gargoyles and chimaeras – were damaged by high-pressure hoses used to fight the fire. Many were already in poor condition because of pollution.

A workshop was set up in front of the cathedral to repair and where necessary replace these statues. Five of the gargoyles (products of Viollet-le-Duc’s imagination) were scanned by computer, and then re-made in limestone.

Inside the cathedral, the most famous sculptures – such as The Virgin of the Pillar and The Vow of Louis XIII – emerged unscathed. But they have all been cleaned and given minor repairs.

The cathedral’s many paintings have also been cleaned. These include the “Mays” – massive scenes from the life of Christ which were an annual gift to the cathedral in the 17th Century from the goldsmiths of Paris.

The return of colour

EPA

EPAOne of the most remarkable changes to the cathedral is the return of colour to the choir and many of the side-chapels.

Here again, the fire offered an opportunity to rediscover the glories that lay beneath decades of crud and soot. Blues, reds and golds have re-emerged, combining with the creaminess of the rejuvenated limestone to create a lightness that must be much closer to the original experience.

The same is true of the stained-glass windows. These were undamaged, but filthy. They were dismantled, removed, cleaned, and returned. The big rose-windows were left alone.

Again, much of what the visitor sees today is not actually medieval – but the product of the medieval imagination of Viollet-le-Duc.

Great organ’s 8,000 pipes cleaned

The great organ – built in the 18th Century – was unaffected by either heat or water on the night of the fire. What did for it was the accumulation of a yellow dust – lead monoxide – in its pipes.

The whole structure – 12 metres high, six keyboards, 7,952 pipes, 19 wind-chests – was disassembled and taken to workshops outside Paris.

Sheep-leather linings were replaced and new electronic controls were added. After reinstallation the instrument was re-tuned – a task which takes several months as each pipe is minutely altered.

On 7 December, the Archbishop of Paris’s first words on entering the reclaimed cathedral will be: “Awake oh organ, Let God’s praise be heard!”

The eight bells of the north tower were also removed in 2023 – a massive operation given their size. They were cleaned and treated, and then returned a few weeks ago. The biggest of the bells is called Emmanuel.

EPA

EPANew chalices and bronze altar

Visitors will also notice a change to the liturgical lay-out of the cathedral, whose altar, lectern and seating were all destroyed. A simple bronze altar has been created, with new chalices for the sacraments.

There are 1,500 new wooden chairs for the congregation, and a new reliquary behind the choir to hold the Crown of Thorns.

New vestments have also been created for clergy by designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac.

Buried 13th Century structure unveiled

AFP

AFPRenovation work at Notre-Dame has been a boon for archaeologists, who have been able to access underground areas that date back to hundreds of years before the cathedral was built.

Among the many sets of bones they discovered are those believed to belong to the Renaissance poet Joachim du Bellay.

Another major discovery was the carefully buried remains of the medieval rood-screen, which originally separated the sacred part of the church from the congregation.

This 11-metre stone partition, built in the 13th Century, contained rich and colourful sculptures depicting the life of Christ. It was dismantled in the 18th Century following a change in church rules.

But clergy clearly hoped the remains would be rediscovered because the parts appear to have been lain with great care beneath the ground. It is hoped they can be pieced together and put on display.

What next?

Despite the success of the renovation, work is not complete. There is still scaffolding around much of the eastern end, and in coming years the outside walls of the apse and sacristy will need treatment.

There are also plans to redesign the esplanade, and to create a museum in the neighbouring Hôtel-Dieu hospital.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Leave a Comment